Affordance and wayfinding in voice interface design

March 3, 2020I wrote a book about voice content and how to build content-driven voice interfaces. Voice Content and Usability is A Book Apart’s first-ever voice design book. You can learn more about what’s in the book or sign up for preorders.

Voice interfaces are becoming increasingly complex and commonplace as the demands of consumers continue to demonstrate a preference for voice-activated search, access to content through voice, and other unprecedented voice features. More and more, we want the same immediacy of a website or mobile application to be present in the voice context, whether that means ordering takeout, paying a credit card bill, or accessing important content. Nonetheless, truly robust voice design requires us to engage in a complete overhaul of the approaches that defined the first decades of web usability when it comes to affordance, wayfinding, and usability.

I would argue, however, that though physical and visual affordances and signifiers certainly are unavailable in the context of a voice assistant or voice-only interface, aural and verbal affordances and signifiers not only exist but are critical for the success of any voice interface, especially when it comes to a fully inclusive experience for disabled users and particularly those with low or no vision. In this article, as the complexity of voice interfaces continues to grow, I outline some of the ways in which we need to envisage and reconsider affordances, signifiers, and wayfinding approaches to ensure as rich a user experience in voice as we would find on a typical website or interface in the physical world.

Affordance and signifiers in voice

The terms affordance and signifier carry great weight in the field of human–computer interaction (HCI) and particularly user experience on the web. In 1966, in his seminal work The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems, James J. Gibson defined an affordance as “what the environment offers the individual,” whether that entails humans in cities or animals in their natural habitats. Twenty-two years later, in 1988, Donald Norman, the originator of the term user experience, went a step further in his book The Design of Everyday Things by defining affordance as a characteristic of an object that helps people understand how to interact with it—in short, an “action possibility.”

As Tania Vieira writes, “affordances help people understand how to use a product.” Usability.gov, in its glossary on user experience, goes further to define an affordance as “when a control behaves as its appearance suggests,” and Natasha Postolovski wrote in 2014 that affordances are a “perceived signal or clue that an object may be used to perform a particular action.” In 2013, however, in his updated edition of The Design of Everyday Things, Norman clarified his original vision for affordances as delineating perceived or inherent “action possibilities” by adding the notion of signifiers, which explicitly communicate where such possible actions should be undertaken.

In that work, he wrote: “Designers needed a word to describe what they were doing, so they chose affordance. What alternative did they have? I decided to provide a better answer: signifiers. Affordances determine what actions are possible. Signifiers communicate where the action should take place. We need both.” In short, signifiers reduce the distance between the truth and perception of what can be done with an interface element.

Do affordances and signifiers exist in voice?

Mark Schenker of Adobe writes the following about voice interfaces, something I found to be an intriguing assessment of whether the concepts of affordance and signifiers even exist in the context of voice in the first place:

“Needless to say, that advantage [of signifiers clarifying to the user that an object’s affordance is true, as in a button’s drop shadow] isn’t present in voice UI. Another challenge is users’ preconceived notion that voice communication is mainly between people and not between people and technology.”

While I agree with the notion that voice communication is an altogether distinct brand of human–computer interaction, I challenge the contention that because voice users are engaging in human conversation, they should be treated any differently from users of visual and physical interfaces. After all, the keyboard and mouse were both interfaces unfamiliar to users in the early days of the personal computer, yet they are so well-known today as to be second nature to computer users. Or, consider the skeuomorphic signifier exhibited by the floppy disk, which is now humorously referred to by the Generation Z cohort as a “save icon” due to their lack of exposure to those historically hardy purveyors of storage. These examples support a cultural, social, and learned foundation for perception of affordances that we can readily see in the voice context.

We have become accustomed enough to learn these elements of our everyday visual interfaces; why shouldn’t the same be true of our voice interfaces too? After all, the “microphone icon” is now universally understood as a signifier of any number of possible interactions, and many users of voice assistants extrapolate the ways they approach conversation in their own devices to others they encounter in the wild—thus facilitating a range of shared practices across the population of voice interface users.

Thus, not only do the concepts of affordance and signifiers exist in voice, it is becoming even more pressing to consider how we provide for voice affordance here and now. The proliferation of voice interfaces, whether they entail voice-activated search or voice assistants like Amazon Alexa or Google Home, readily indicates that users’ expectations—as well as their awareness and expertise—are rapidly evolving when it comes to how they interact with voice interfaces.

Aural affordance

Consider the first and most important interface we interact with on a regular basis: the world around us. For disabled users navigating through this world-sized user interface, certain affordances are indicated through complex signifiers that are aural and verbal in nature and that aid our wayfinding and navigation.

In the real world, aural affordance is articulated through signifiers that run the gamut across the most simple of sounds to the most layered of soundscapes, only some of which contain interpretable verbal content. In New York City, many office buildings have dispensed with the typical mechanism of selecting a floor within an elevator car itself, rather relegating that feature to “floor pickers” outside of the elevator that, typically in a soothing yet monotone voice, indicate which elevator the user should direct themselves to, often repeating the chosen floor back to the user. These signifiers are a fixture of daily corporate life in many major metropolises. But many aural affordances can also be articulated without leveraging the spoken word at all.

To inspect a more nuanced example, consider the melodies and jingles ubiquitous in the Tokyo rail network and the Seoul Subway in Japan and South Korea, respectively, which are designed specifically to enhance the ease of use of these transit systems. On many of Tokyo’s rail lines, stations are distinguished by unique melodies that are immediately identifiable and allow commuters to grasp their current location. (The Tokyo rail network’s jingles per station were also designed to calm stressed commuters as well, which is a fascinating idea whose exploration lies well outside the scope of this blog post.) Meanwhile, the Seoul Subway plays a characteristic jingle at line interchanges to notify users that they should disembark to transfer to a different line.

The interfaces that decorate our real-world experiences can be made particularly accessible by trafficking in both visual and aural affordance and matching signifiers, as we witness at American crosswalks whose signifiers not only toggle between icons but also play distinctive sounds immediately recognizable for disabled users. Ensuring that this faithfulness to affordance does not deter or limit the experience of users who may not have the same ability to access the action predicated by that affordance is a key facet of the concept of universal design, as described by Margit Link-Rodrigue.

These signifiers are typically positioned such that they can easily be considered metonymously representative of the interfaces they govern, such as the floor pickers standing outside the elevators they appear to manage, iconography displayed and loudspeakers perched on a signpost above a zebra crosswalk, and Japan’s train jingles heard throughout the entirety of the vehicle. All of these signifiers share one thing in common: they help the user understand what their next interaction with the interface in question should be: Cross the street or wait? Get off this train or stay on?

Expressing affordance in voice interfaces

With evolving expectations and knowledge in society, the keyboard and mouse are artificial and learned interfaces and have, through their common manipulation by more and more computer users, narrowed the gap between the user’s understanding of how to work with them and the actual approach required to operate them. In the same way, voice assistants like Amazon Alexa and Google Home are rapidly being learned and understood by a growing range of users around the world, as well as the interfaces contained therein.

By putting voice interface elements in the correct context and relying on prevailing tropes to guide our interface design, we can leverage existing foundations to design effective voice interfaces. Consider, for instance, a typical telephone hotline with an automated responder. Because we are so familiar with the model of “press X for this action,” the sentence pattern used by hotlines has become such a recognizable signifier that we can respond to any similarly designed interface with an appropriate response, even if there are slight differences from hotline to hotline. We have learned how to better perceive this particular affordance.

Because there are no visual or physical objects that we can craft or manipulate in voice design, users must instead extrapolate from utterances. Utterances can have affordance too, by their mere presence (“the interface is saying something, so I should listen”) and by virtue of their intonation (“Do you want to confirm this order?”) or character (“Oops! I didn’t get that, sorry”), and they can signify what actions should be performed next, often without necessarily requiring a significant amount of help text contained therein thanks to previously learned behaviors. For instance, consider the most common typical queries heard at a local diner:

Fries or salad?

Coke or Pepsi?

Cream or sugar?

To stay or to go?

Based on the pattern embraced by these utterances, we can extrapolate given that only two options are available to select, presented in the form of a clarifying query (affordance), and what answer we need to provide and how (signifier) in order to perform an operation successfully: a short response of our own that mirrors one of the options listed.

The simpler the structure of an utterance, and the more repetitively it is used, the higher the affordance (in Norman’s original sense) of a voice interface element. It is for this reason that I often recommend that voice interface designers consider how the most simple of affordances in visual interfaces can underlie complex interactions in voice interfaces without introducing too complicated of behavior. In forestry, for instance, dichotomous keys (also known as single-access keys) are helpful in classifying trees encountered in the wild. This is not only because the same mental model can be applied on each and every use but also because they reveal information incrementally and parsimoniously given the granularity of earlier revelations in the user flow. Option menus in phone hotlines leverage precisely the same approach to winnow the user’s requirement to the most essential doable task and route them correctly, providing more specific signifiers each step of the way.

In short, just like in visual and physical interfaces, the more repeatable and recognizable—i.e. consistent—interface elements are, the higher their affordance in the aural and verbal context. And it is precisely this repeatability that aids quick learning of interface and more rapid extrapolation to other voice interfaces as well. In many senses, a conversation with a voice interface is a progressive narrowing from a range of possible actions (the all-encompassing “microphone icon”) to increasingly granular affordances that the user can perceive correctly and respond to accordingly.

Dealing with navigational complexity in voice

In recent years, voice interfaces have become increasingly structurally and hierarchically complex, particularly once they move beyond simple one-off tasks to handle a richer array of functionality. A typical credit card company’s voice assistant, for instance, may provide other capabilities in addition to checking balances and paying bills such as reporting a card as lost or stolen, which requires a completely distinct flow for users to travel. In an environment without breadcrumbs or persistent navigation menus by design, how can users ever know where they are in a particular flow?

Complex actions that jump up and down hierarchical levels within a voice interface require such interfaces to focus a great deal of attention on wayfinding. As we saw in the previous section, and as I’ve written previously, not only is the design of the repetitive and standardized language used to express voice affordance important; the repetitiveness and simplicity of the decision flows that users traverse are also key to the success of any voice experience.

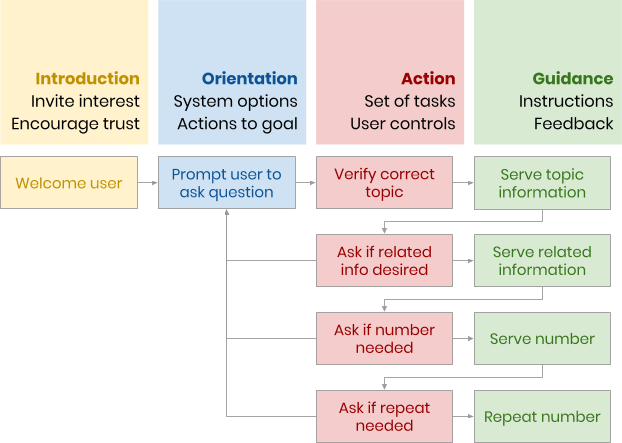

Consider, for instance, the conversational flows we designed for Ask GeorgiaGov, the first Alexa skill for citizens of the State of Georgia that I’ve covered extensively in the past. This map of user flows is based on key moments in conversational interfaces outlined by Erika Hall in her seminal book Conversational Design, with a three-level hierarchy for each type of accessible content: a topic, related information about that topic, and a phone number. At each node, the user can navigate back to the root level and restart their interaction.

Voice affordances need to support wayfinding

Tania Vieira describes four types of consistency identified by Don Norman: aesthetic, functional, external, and internal. When designing voice interfaces, we need to ensure that all affordances exhibit clear consistency, whether that means with the user’s expectation of how the interface should work based on their learned behaviors (external and functional consistency) or with other affordances for actions present in the interface (internal consistency).

When translating web content to voice content, links are impossible to distinguish from other uttered text, as I discussed in my recent article about conversational content strategy. Other aural affordances are required to allow the user to understand that particular utterances can trigger a state change in the application. Consider, for instance, the fact that many phone hotlines and other voice interfaces adhere to a relatively minimal list of possible responses that are universally understood:

Back

Next

Skip

Exit

And to elicit these utterances from the user, voice interfaces will often remain faithful to a particular structure in their elocution:

To go back to the previous step, say Back

To go to the next step, say Next

To skip the next step, say Skip

To start over, say Exit

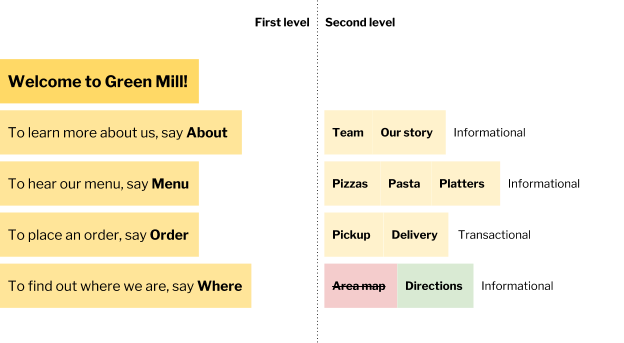

In addition, voice interfaces often exhibit sequential order in a particular way to limit confusion. Consider a pizzeria who accepts orders through a voice interface on an Amazon Alexa or Google Home, as I’ve covered in previous examples:

Say something like Pepperoni, Mushroom, or Pineapple

Was that Pepper or Pepperoni?

Each time the voice interface solicits a response from the user, the responses are as brief and clear-cut as possible, and the potential range of responses that the user can issue in response is similarly expressed in as parsimonious a fashion as possible. Though this sort of consistency can seem artificial for users accustomed to human conversation, it has now been learned by a broad set of voice interface users what uttering “Exit” will do despite never saying such a terse command in authentic dialogue. Users also now understand when they are being prompted for a response based on how the surrounding language is crafted (consider the imperative “say” above and the way lists are articulated), even without the visual signifiers that devices like Amazon Alexa use to demonstrate they are seeking a user-generated response.

This is why I also encourage voice designers to spend a greater amount of time on the highest-level navigation in a voice interface: the system menu. Not only does the system menu serve as the entry point for the user; it also represents the earliest establishment of key actions and operations possible within the interface—as well as the manner in which every single other menu works. All voice interface users will rationally extrapolate from that initial system menu to understand how they should interact with the interface at later moments:

Interface: Welcome to Green Mill! We're happy to serve you today. To order, just say Order. If you want to go back at any point, just say Back. To start over, say Start over.

[Some minutes later]

User: Back, I mean, start over!

Voice affordances need to abstract an information architecture

To return to our earlier credit card example, when a conversational interface in the voice context begins to engage in a complex and hierarchical information architecture, wayfinding in such voice interfaces is key. But wayfinding presents particular obstacles because of its lack of a visual component in the voice context. For instance, when there are no breadcrumbs or URL bars in an Alexa device, how do you know truly where you are in the interface without having to ask?

As such, affordances in voice that provide for wayfinding and allow for rich navigation up and down the decision tree need to be able to offer users the ability to abstract a structure in their mind, or at least to ascertain where they currently are in the interface itself. In the final (and perhaps most challenging) stage of the classic computer game Myst (spoiler alert), players are tasked with memorizing a series of cardinal directions expressed through characteristic sounds and inputting that series of directions into a vehicle that transports the user to the location where they can win the game. Our wayfinding approaches in voice interfaces should be simple enough that a sheet of paper to track how far we’ve come isn’t necessary.

This means that when it comes to translating our web-based design approaches to voice, we need to be careful to ensure that our interfaces remain navigable with simple information architectures without overly complex hierarchies—or that we provide easy means for the user to map their visual sense of the interface to their interactions. Consider, for instance, the fact that many phone hotlines and Alexa skills simply repeat the “main navigation” bar’s available links at the end of every response issued to the user, which may be more verbose but can support particularly confusing interfaces:

I heard you say Pineapple. To add the topping to your Large Pizza, say Add. To go back to the list of toppings, say Back. To start over, say Start over.

As I discussed in a previous article about information architecture in conversational interfaces, the traditional hub-and-spoke networks represented by drop-down navigational menus and sitemaps are unworkable in a voice context. Voice interfaces necessarily must be highly linear and one-track-minded. When complexity does occur, providing navigational schemes explicitly and repeatedly throughout an interface establishes consistency akin to the menu bars found across all Mac and Windows programs (“File, Edit, View”). In this way and others, we can bridge the abyss between web and voice interfaces without overly prestiging one over the other.

Conclusion: Utterances are affordances too

This brings me to my final point, which aims to harness all of the thinking about affordance and bring it into the voice context. When we consider typical affordances in the web context, such as underlines for hyperlinks, a drop shadow for buttons, and distinct colors for success and failure messages, we normally do not consider text to be part of that milieu, despite the vast amount of help text and interface text that decorate our web interfaces and are also, as such, affordances in their own right.

In the voice context, utterances are perceived affordances too, often generated by the interface itself as help text. All form elements on a website, whether represented by a

<select><select>Voice interfaces are reinventing user experience in more ways than just usability testing approaches and accessible alternatives. They are reconstructing from the ground up the overly visually and physically inspired terminology we employ on a daily basis to describe user interface design. They are also introducing new ways of thinking about user experience that we need to take into account as we design for a growing number of channels and form factors, such as the aural and verbal cues that are not only afforded to interface elements in the real world and in existing voice interfaces but also how those affordances are being learned at an incredible pace by users of all backgrounds.

In just a few short years, will we have learned voice interfaces sufficiently—or will voice interfaces have learned enough about us and how we employ language—that the hotline-style “press three to hang up” or “say Exit to go home” will go the way of the floppy disk? As the notion of affordance expands beyond the physical and visual and into the aural and verbal, the range of opportunities for a new sensibility about user experience in the voice context is staggering but not without its usability pitfalls. In the meantime, we and the voice interfaces we design have much to learn about one another.