Building usable conversations: Conversational content strategy

February 11, 2019I wrote a book about voice content and how to build content-driven voice interfaces. Voice Content and Usability is A Book Apart’s first-ever voice design book. You can learn more about what’s in the book or sign up for preorders.

This is part of a series of articles on conversational content strategy, with installments about conversational interfaces, information architecture, design, usability testing, and Ask GeorgiaGov, the first voice interface for residents of the state of Georgia. Reprinted from the Acquia Developer Center with permission from DC Denison (Senior Editor, Acquia).

In this fourth installment of our series on conversational usability, we're turning our attention to conversational content strategy, an underserved area of conversational interface design that is rapidly growing due to the number of enterprises eager to convert the text trapped in their websites into content that can be consumed through voice assistants and chatbots.

For those working with content management systems like Drupal, a content strategy that cuts across both the web and conversational interfaces is of paramount importance.

In conversational interfaces, working with content forces us to take a step back and consider from a high-level perspective how our content should be written, structured, and managed. Fortunately, as we'll see throughout this column, those who are working with structured content in content management systems are already at an advantage. Moreover, these prescriptions primarily relate to informational rather than transactional conversations. Nonetheless, all of the lessons here can apply to anyone interested in working with conversational content.

The importance of an omnichannel content strategy

Content strategy traditionally involves the planning, creation, and governance of content and has historically referred primarily to web content. Nonetheless, with the advent of the channel explosion and the proliferation of new consumer devices, content strategy can now be applied to any device, any channel, any form factor, and, indeed, any user experience conceivable. For those interested in conversational content strategy, however, emerging approaches introduce significant complexities into the equation.

As we learned from the first and second installments of this series, conversational content differs considerably from web-based content, especially due to the low verbosity tolerance of conversational content. Whereas the web can traffic in large swaths of text without interruption, conversational content typically involves bite-size portions of text, particularly on voice assistants. This is a relevant issue for chatbots as well, as everyone often saves a particularly long text message for later reading.

I've always espoused a content-first approach to the development of any digital ecosystem that juggles multiple experiences and straddles multiple devices. This is because the content that you exhibit through channels other than the web is crucial not simply in the messaging that it conveys but also in the manner in which it is delivered. For instance, a typical FAQ page on a website would translate well to a conversational context, but a privacy policy or a terms and conditions document certainly wouldn't.

For this reason, when undertaking any project that encompasses conversational content, it is important to take stock of your existing digital ecosystem and the devices and channels that you plan to serve. An omnichannel content strategy that takes into account all of the distinct devices and channels that your organization deals with will provide the underpinnings for a robust approach to content. And this begins with a holistic view of your roadmap and a key question: Will you provide unified content in a cross-channel fashion or instead delineate specific content for each channel?

Cross-channel content or content by channel?

Conversational content is unique among content presented through modern channels because its very nature necessitates a different approach to structured content. For instance, while a privacy policy is easy to skim on a laptop, tablet, or mobile device (within reason), it is not "legible" in the conversational sense (see next section) on a voice assistant or chatbot. For this reason, organizations should consider their editorial requirements and technical needs to answer this fundamental question.

Many organizations lack a fully funded editorial team, particularly in the public and non-profit sectors. It can be difficult to justify writing multiple versions of content when operating on a shoestring budget. On the other hand, organizations with large editorial teams that are capable of prolific content production may wish to consider the advantages of distinct pieces of content that vary per channel. A privacy policy page could remain the same on a website accessed through multiple devices while a crisper summary of the most important legalese is provided through Amazon Alexa or a textbot.

Consideration of an omnichannel strategy is essential when it comes to the technical ramifications and governance impacts as well. Typically, it is much easier in traditional content management systems like Drupal to manage a single version of content that can be distributed easily across all channels and devices through a mechanism such as decoupled Drupal (a book on the subject was just written by this author). In addition, organizations should give particular attention to the maintenance costs of content that differs on a channel-by-channel basis, as large databases of content with multiple versions of a single content item housed therein can quickly become unwieldy and unmanageable.

Owing to these editorial and technological considerations, I generally recommend that organizations first consider a unified content strategy that attempts to retain cross-channel harmony by focusing on both conversational and web-based content while writing the copy to begin with. By preparing your editors for an omnichannel future by requesting that they write content that can be appropriate for any device, with guidelines on how to do so, you will receive dividends in the future with regard to the governance of your content.

However, many organizations, for one reason or another, must opt for an approach that delineates content based on its channel. In Drupal, for example, this can be done in a decoupled fashion by designating custom fields that only apply to the presentation of a content item if a particular device performs a request to the content management system. For instance, an article in your CMS can have a "Body" field for websites and a separate "Body" field for conversational interfaces. Exercise caution, however, as this can rapidly lead to struggles with maintainability and governance.

Conversational content legibility

One of the two most crucial questions to ask yourself when creating content for a conversational experience—especially if you are utilizing a content strategy that unifies all content across channels—is whether it is legible from a conversational point of view. Consider, for example, the differences between a longform article and a simple set of FAQs, a distinction covered in the first post in this series highlighting web vs. conversational content.

After all, content structured in a certain way lends itself favorably to certain types of user experiences. A longform article with a title and (very lengthy) body is something we would typically expect to see in a website. Meanwhile, an FAQ page, due to its relative brevity and scannability, is something we might find on a smartphone application or, due to its low verbosity, on a conversational interface.

This is particularly true for voice assistants. Whereas chatbots and other messaging bots may benefit from the ability to display more text (with the exception of SMS, which will divide content into less legible chunks) including multiple paragraphs if necessary, Amazon Alexa and Google Home users cannot wait for the entirety of those paragraphs to be recited as spoken words. If you choose to divide content on a per-channel basis, you should consider having two separate versions of content depending on the verbosity tolerance of your conversational interface.

However, if you have a single manifestation of your content that should be replicated across all channels, you may need to perform a conversational content audit (see section after next) and rewrite some of your content to be more appropriate for interfaces where overly lengthy text is damaging to the user experience. Consider the following examples.

If your content is relatively long and could do with a summary, it may be useful to distinguish between the summary and the full version of the content, because that can be an easy but straightforward way to provide conversational and web versions of your content. A summary can be uniquely valuable both for structured web content and for maintaining a more manageable size for your conversational content.

Full text (web version): With twenty locations in Minnesota and others in Kansas and Indiana, Green Mill is a culinary star of the Midwest. We cook with only the freshest ingredients and have many options for gluten-free customers.

Summary (conversational version): With twenty locations in Minnesota, Green Mill is a culinary star of the Midwest. We use only the freshest ingredients.

If your content is relatively short—indeed, too brief to have a separate summary field—then it is possible to simply replicate your content across to the conversational interface, retaining a single vision of your content, without modifying it.

Our options include gluten-free, dairy-free, kosher, halal, vegetarian, and vegan menu items:

In a conversational context, you can simply add available actions to the end of your content to offer the user the ability to interact with the interface.

Our options include gluten-free, dairy-free, kosher, halal, vegetarian, and vegan menu items. Say List for more.

Meanwhile, if your content is uniquely well-suited for use in a conversational interface, such as an FAQ page, it is possible to reuse the same content without any modification at all.

Q: What are today's deals? A: Today's deals are 50% off large pepperoni and 12 dollars for a medium one-topping pizza.

Yifan: What are the deals for today? Green Mill chatbot: Today's deals are 50% off large pepperoni and 12 dollars for a medium one-topping pizza.

By inspecting your content with a magnifying glass, you can make crucial decisions about how your content should evolve. If you have undertaken a content-first strategy and most of your content is already written, then it may make more sense to adjust content where you see fit and experiment with strategies like those covered above, such as summary fields and abridged content. If you have not yet written your copy, you can choose whether to maintain unity across all of your content or to distinguish it based on the channel that is its destination.

Conversational content discoverability

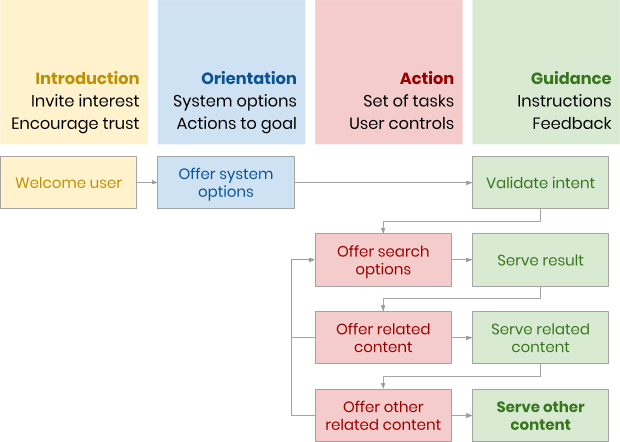

As discussed in the previous installment of this series concerning conversational design, discoverability of your content is a key component of ensuring that an organization's content strategy succeeds. After all, we can work many hours on guaranteeing the legibility of our content while simultaneously, and unintentionally, inhibiting the discoverability of our content. In the previous post, to address discoverability in a systematic way, we discussed the need for flows that are guided and unidirectional.

Nonetheless, it is also essential to design flows that do not obligate the user to travel too deeply down the hierarchy, because as a user travels down a conversational flow, content becomes less discoverable with each movement. Consider the diagram above, which depicts a flow that repeatedly serves related content to the user without clear routes to return to earlier portions of the interface. Eventually, like in natural conversation that becomes overly repetitive, the user becomes disengaged and discouraged from finding what they were looking for.

For this reason, it is always important to pair a strong understanding of the information architecture we have conceived (i.e. navigation options that never maroon the user or leave them stuck in limbo and indications of how the user can travel up levels or to the interface's entry point) and a robust approach to content strategy (i.e. content items that are brief and easily relatable to other proximal content items) in order to achieve conversational discoverability. The conversational landscape proves again the battle-tested adage that content strategy and information architecture are inextricable from one another in any medium.

Performing a conversational content audit

If you have a substantial amount of content that was written before you began implementing a conversational interface, or if you plan to write a considerable amount of copy that will make its way to a voice assistant or chatbot, performing a conversational content audit can be a revealing means of finding tricky obstacles or unusual oddities in your conversational content that can make it more difficult to use or consume.

While in chatbots and other messaging bots, instructions can be followed and links can be clicked, voice assistants and other voice-driven interfaces lack this luxury. This means that any important auxiliary information, such as a description of a topic only accessible by referencing a link, or a file download indicated by a parenthetical about an available PDF, will trip up the user and obfuscate an otherwise seamless user experience.

As we know from previous entries in this series, conversational interfaces present obstacles that need to be addressed when transforming web content into conversational content. In addition to brevity, which we have mentioned before in this post, it's essential to consider what happens when users are faced with web-only features such as references to inaccessible locations (e.g. "Click here to learn more") or parentheticals that are nonsensical in a conversational context (e.g. "PDF download").

For this reason, I recommend you take to your content with a fine-toothed comb, looking for traits that may impact conversational legibility and discoverability. When it comes to legibility, for instance, we can evaluate content by reading it aloud to find weaknesses, inserting additional context when a link leads to another page (e.g. "read more about this here" replaced with a sentence that places the call to action in the context of relevant information) or an image lacks descriptive text, and removing copy that is difficult to interpret in a voice assistant setting. Some content will doubtlessly also be overly verbose for a voice assistant and should be divided into more easily digested portions accordingly.

Inspecting your content a second time, this time with a lens on conversational discoverability, will likely reveal long-standing issues in information architecture and content strategy that hinder the user experience. You may find, for instance, that a particular instruction placed after the reading of a piece of content may not be prominent enough to galvanize the user into a response, or that the relationships between pieces of content that are employed by the interface to improvise a hierarchical structure in the user's mind are overly complex and difficult to remember. In this case, rather than having content that confuses the user, you may have content that is impossible to find in the first place.

There is no single optimal way to perform a conversational content audit, as your organization's needs will likely differ from others'. Nonetheless, in coming columns in this series, we'll take a look at a case study of a voice assistant currently in production and dive into the conversational content audit taken during the project's progression. Stay tuned for more insight into how a conversational content audit can help you reinvent your content.

Conclusion

A successful content strategy for conversational interfaces comes from a content-first approach that considers how that content will be manifested in a conversational form (among others). One of the first decisions you will need to make is whether to retain unified content or per-channel content. For organizations already working with a web content management system such as Drupal, this transition can be made easier thanks to structured content and an omnichannel focus. For organizations who are writing content from scratch, particular attention should be paid to the content's conversational legibility as well as its discoverability.

In the next installment of this series on building conversational interfaces, we train our eyes on usability and user experience, with particular scrutiny on how to perform successful usability tests of a wide variety of conversational interfaces. Many of our preconceived notions about usability derive from web usability, which cannot be applied as-is to conversational usability. In the next column, we'll dive into some of the challenges that make conversational usability such a unique problem and proven techniques to ensure all of your end users can succeed in your conversational interfaces.